Beethoven in Beijing

Description

Streaming now available on PBS Passport

The catalyst for our story is a momentous chapter in U.S. history that would shape the course of global affairs into the next century.

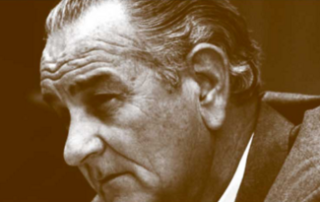

The groundbreaking 1972 trip of President Nixon to renew relations with China serves as a backdrop to explain how it came to be that the Philadelphia Orchestra was the first American orchestra sent to perform in the People’s Republic of China.

We rely on a trove of archival materials to build a story that spans nearly a half century. At the same time, we weave into the narrative observational footage from recent years to convey how this film, while rooted in the past, also transports the viewer into the present.

The first act focuses on the 1973 tour, relying on firsthand accounts by veteran musicians and other participants to narrate the story. We surround their interviews with archival material, such as photographs, news footage, and audio recordings.

The second act explores how the Orchestra has built cultural bridges with Chinese musicians and maintained its ties to China. The visual storytelling in this section combines archival assets with recent tour footage.

The final act, which examines how the Philadelphia Orchestra is turning to its past in China to bolster its precarious present, is largely told through observational footage and interviews, with some archival photos and video.

Through the arc of the story, two conductors serve as narrative bookends — the legendary Eugene Ormandy from 1973 and his charismatic, contemporary successor, Yannick Nézet-Séguin. Three Chinese collaborators with today’s Orchestra emerge as central characters whose personal journeys epitomize the revival of classical music in China: Oscar-winning composer Tan Dun, 63; pianist Lang Lang, 37; and composer Peng-Peng Gong, 27.

The film opens in the present with Nézet-Séguin and Lang Lang waiting in the wings at the National Centre for the Performing Arts in Beijing. From here, we step into the past. It is 1972. China and the United States are on the threshold of history. Nixon and Premier Zhou Enlai are working to end decades of isolation and animosity. America needs to win over the Chinese people and dispatches musicians from the Philadelphia Orchestra as cultural ambassadors. Chinese audiences have never heard an American orchestra. The tour comes in the midst of the Cultural Revolution, when western classical music is banned in favor of revolutionary works. As a Chinese composer recalled, he was “seduced” by the sound of the Philadelphians performing the forbidden music of Beethoven.

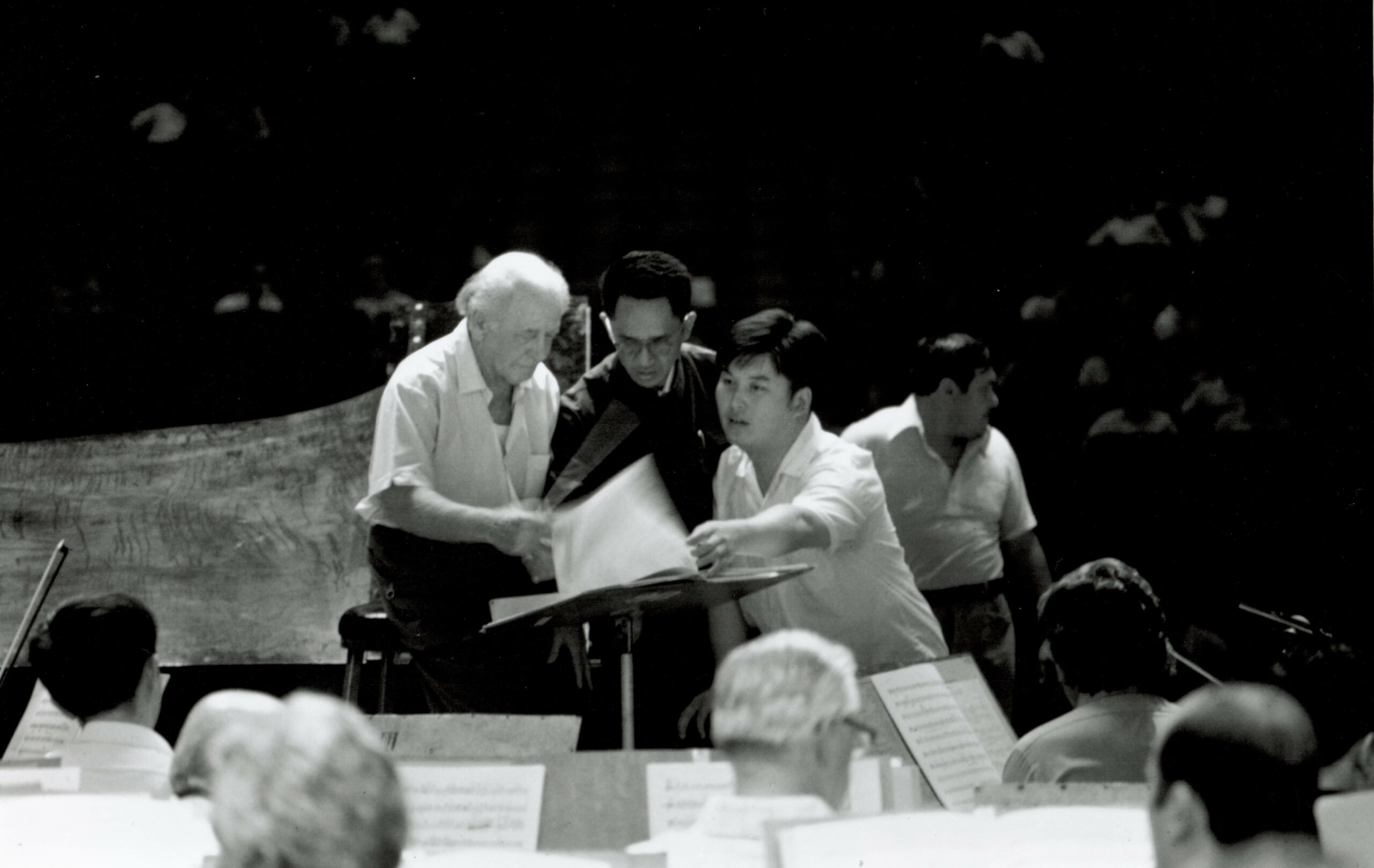

Film of Nixon’s visit is followed by memories of the 1973 tour from American and Chinese musicians. There are small dramas—Mao’s notorious wife, Jiang Qing, insists that the orchestra to play Beethoven’s Sixth Symphony, not the nationalistic Fifth—and audiences seem subdued, but the trip is a success. Ormandy conducts a rehearsal of Chinese musicians. At the airport, he says: “Through great music, many people became friends, who were hated enemies.”

Mao dies three years after the tour. The Cultural Revolution ends. In China, “Beethoven Fever” begins.

Act Two focuses on the revival of classical music in China, fueled by pent-up demand after the lifting of Cultural Revolution restrictions; a booming economy providing families with disposable income to lavish on their only children; and governmental emphasis on music education in Chinese schools.

Viewers are introduced to three musicians who would each develop close ties to the Philadelphia Orchestra — Tan Dun, Lang Lang and Peng-Peng Gong. Because of the span of their ages, their experiences dramatize different inflection points in the revival of classical music in China since 1976.

We meet Tan Dun, who was a teenager working on a commune during the Cultural Revolution and enters the Central Conservatory of Beijing in 1978, a class that came to symbolize the rebirth of the art form. We meet a teenage Lang Lang, who travels to Philadelphia to study at the esteemed Curtis Institute of Music. In 2001, as a 19-year-old, he returns to Beijing to make his professional debut back home with the Philadelphia Orchestra at the Great Hall of the People.

And we meet composer Peng-Peng Gong, who lives out the unfilled dreams of his father by moving to New York as a fifth grader to attend The Juilliard School.

Act Three opens with the camera lingering over an old photograph of a packed audience at the Academy of Music and the voice of Conductor Eugene Ormandy, speaking at the National Press Club in 1974 and warning: “All orchestras are really suffering today.”

This archival material, uncovered at the Library of Congress, serves as a visual and audio bridge, dramatizing how the pressures facing all American orchestras today date back decades. In contrast to China’s current embrace of classical music is America’s waning interest, epitomized by the Philadelphia Orchestra’s unprecedented bankruptcy filing in 2011.

In the midst of financial hardship, the Philadelphia Orchestra hires the dynamic Nézet-Séguin as artistic director. He speaks enthusiastically about the excitement he feels from younger audiences in China, where we see him signing autographs like a rock star. In contrast, a Philadelphia school principal tears up as she recalls her struggle and eventual success at saving her school’s music program from an unlikely white knight — Lang Lang, whose foundation donated keyboards and funding for piano instruction.

Tan Dun’s remarkable career epitomizes the cross-cultural connection. He is seen accepting the 2001 Oscar for best original score for Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon. We travel with him to Hunan for a hometown premiere by the Philadelphians of his multimedia symphony Nu Shu.

The film concludes with back-to-back performances that illustrate how the cultural bridge between China and the United States no longer travels only in one direction.

In Philadelphia, Peng-Peng Gong premieres a new symphony at a side-by-side concert of the Philadelphia Orchestra and the Shanghai Philharmonic.

At a VIP reception at Beijing’s National Centre for the Performing Arts, Nézet-Séguin marvels at the confluence of an American orchestra, Canadian conductor and Chinese chorus in Beijing: “Beethoven would just not have believed it.” In the hall, he conducts the Ninth triumphantly.

Filmmakers:

Jennifer Lin and Sharon Mullally (Co-Directors)

Sam Katz (Producer)

Film Website: https://www.beethoveninbeijing.com/

Film Stills