FREE CHOL SOO LEE

Description

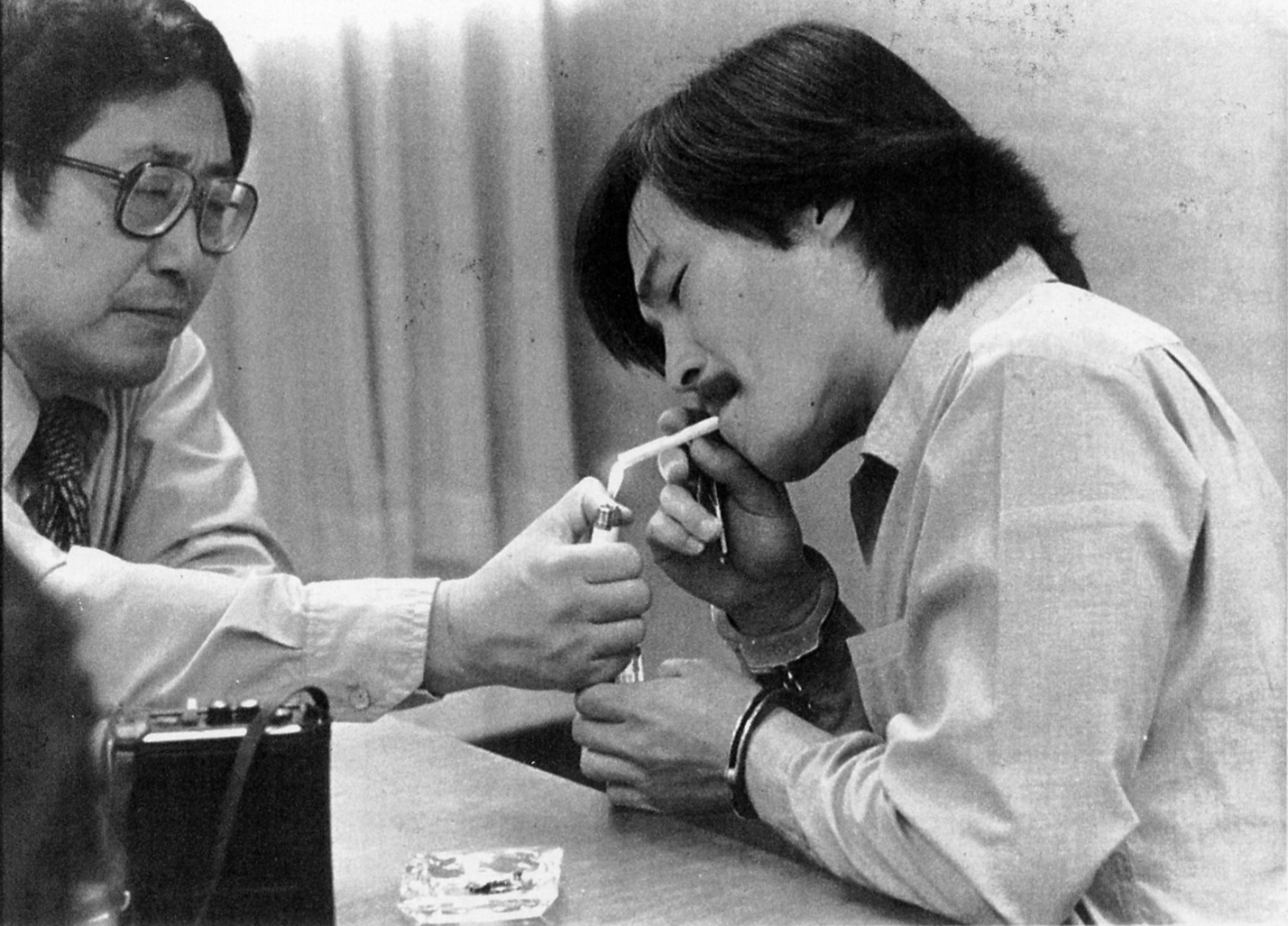

We are greeted by the static lines of a 1983 TV broadcast that eventually clear up and show our interview subject, Chol Soo Lee, a handsome Asian man wearing prison blues and shackles. “A lot of people say, uh, I was not an angel on the outside,” he says, smiling broadly, his eyes piercing. “At the same time, I was not the devil. But whatever I was on the outside does not justify framing a person to put him in prison for a murder he did not commit. That is no excuse.”

Our story rewinds. On a Sunday evening in June 1973, a gunman pumps three bullets into a Chinatown gang leader on a crowded street corner, killing the man. Four days later, San Francisco police arrest Chol Soo Lee. The 20-year-old says he’s innocent. He’s Korean and wouldn’t be wrapped up in the Chinatown gang wars that were seeing a dramatic uptick in violence and were starting to affect tourism. But his friend Ranko Yamada is worried. The college sophomore tries but fails to raise money to hire an attorney. She is right to worry. Based on the eyewitness testimony of three white tourists, a jury convicts Lee of first-degree murder.

Once in prison, as a lone Asian, Lee is vulnerable. He quickly learns how to survive in the gladiator-like environment. But four years into his sentence, on Oct. 8, 1977, a neo-Nazi inmate attacks him with a knife in the prison yard. Lee kills his assailant, claiming self-defense, but he is charged with murder. He will face the death penalty.

Around this time, the Sacramento Union’s chief investigative reporter, K.W. Lee, hears about the case and conducts a six-month investigation. The journalist and prisoner, both immigrants from Korea, meet and quickly establish a rapport. Under the series headline, “Alice in Chinatown,” K.W. exposes gaping holes in the conviction of Chol Soo Lee. He finds that Chol Soo’s own defense attorney failed to object when the arresting police officer identified Chol Soo as “Chinese” during the murder trial.

K.W.’s stories also humanize the convict, telling the saga of a bewildered Korean immigrant boy. Chol Soo, who had grown up with his aunt and uncle in Korea, comes to San Francisco at age 12 to reunite with his mother, who had been banished from her family for having him out of wedlock. Mother and son clash at home. At school, he is bullied; he fights back and lands in juvenile hall. Later, he is sent to a state mental hospital, where he is mistakenly diagnosed with schizophrenia. He becomes a chronic runaway.

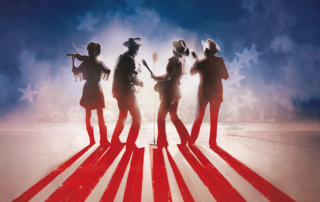

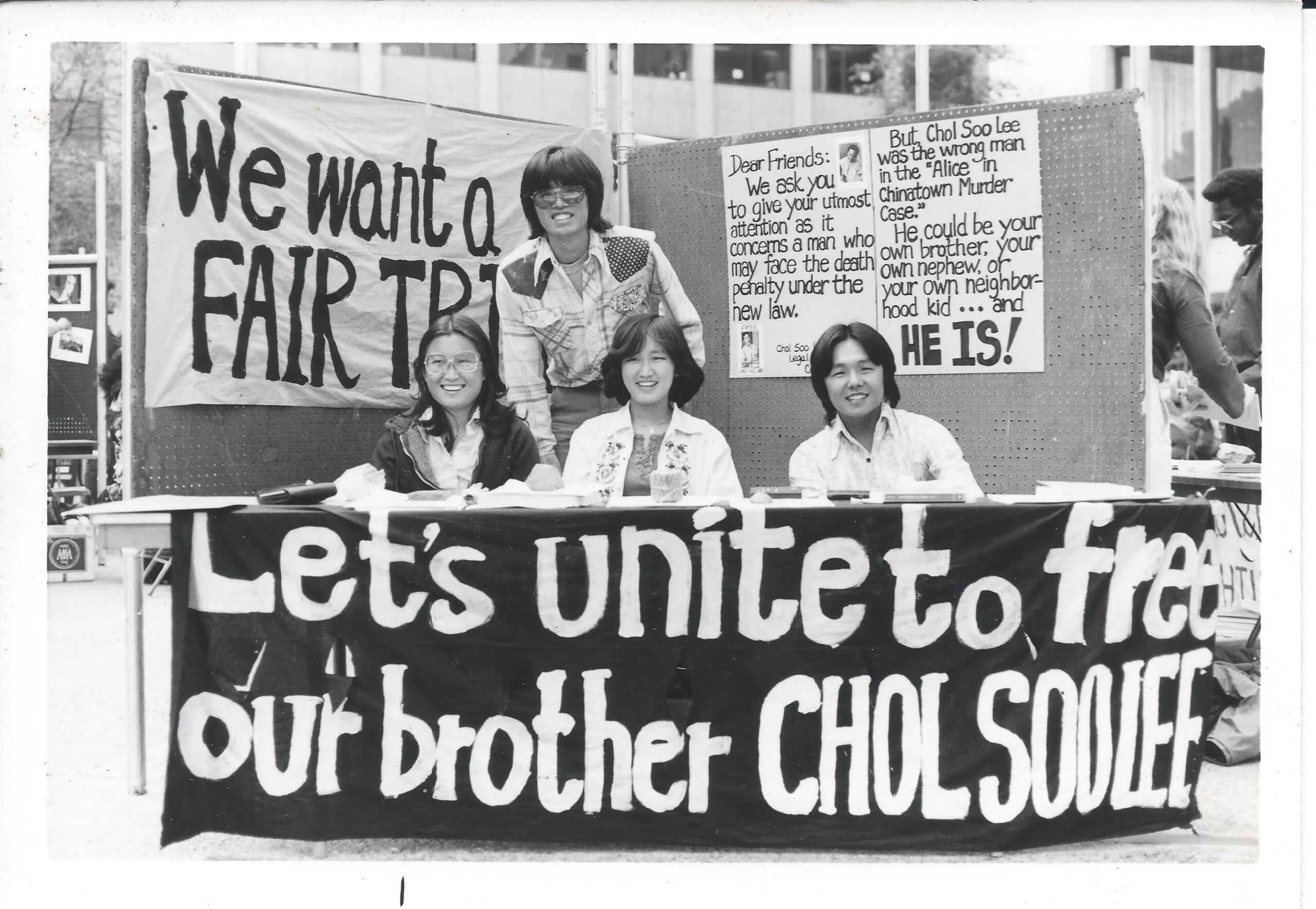

K.W.’s retelling of Chol Soo’s nightmarish version of the American dream touches not only other first-generation Korean Americans, but also third-generation Japanese and Chinese Americans. For the first time, members of these disparate groups unite under a collective identity, as Asian Americans. Young activists with their feathered locks and bell-bottoms stand alongside Korean immigrant grandmothers in traditional Korean silk dresses at courthouse protests. Church collections, college dance parties, and hot links sales — all these efforts raise more than $100,000 to hire renowned criminal defense lawyers, including Leonard Weinglass who famously represented the Chicago Seven. They are joined by a young attorney: Ranko Yamada, who was inspired by the case to go to law school.

In 1979, a Sacramento court overturns the Chinatown murder conviction in a rare habeas corpus victory. But just a month later, Chol Soo is convicted for the prison-yard slaying and sentenced to die in the gas chamber. Activists refuse to give up. When the San Francisco D.A.’s office decides to retry Chol Soo Lee for the Chinatown murder case, his supporters pack the court and make sure the jury knows they are watching. The jury acquits Chol Soo of the original Chinatown murder, and an appeals court reverses the prison-yard murder conviction. In 1983, after 10 years in prison, a 30-year-old Chol Soo Lee walks out of the San Joaquin County jailhouse and into the warm embraces of his most ardent supporters — and also the probing mics and cameras of TV news stations.

In the weeks after his release, Chol Soo goes on a tour to thank his supporters, like a celebrity. He volunteers at a Korean nonprofit, determined to pay the community back. Supporters help the ex-con get jobs, but he loses one after another. He starts to feel the effects of institutionalization and also the great pressure to live up to the symbol he has become. He soon becomes addicted to cocaine. Thanks to the tough reputation he gained in prison, Chol Soo, at age 39, is hired by a Chinatown gang to torch a house. But he botches the arson, and suffers second- and third-degree burns to 75 percent of his body. He is terribly disfigured and suffers disabling injuries.

After testifying against the gang who hired him, he goes into witness protection, often calling K.W., who has become a father figure to him. In these intimate calls, he comes clean about the demons in his life, not only from his years of incarceration but from his childhood with an abusive mother. By 2004, he returns to San Francisco and wants to redeem himself in the eyes of the community that saved him. He speaks publicly at colleges and youth centers about his case. He boasts that many of the activists who came to his aid went on to become public defenders and community leaders. He tells audiences that he himself is no hero; he is just a human being. On Dec. 2, 2014, Chol Soo Lee passes away at age 62. He had refused life-saving surgery for internal injuries related to his burns. At his funeral, inside a modest Buddhist temple in San Bruno, activists gather one final time to chant for their brother: “Free, free Chol Soo Lee!” The one-time protest cry is now an elegiac farewell.

Website: https://www.fcsl-film.com/

Trailer

About the Directors

DIRECTOR/PRODUCER – Julie Ha

Julie Ha’s storytelling career spans more than two decades, in both ethnic and mainstream media, with a specialized focus on Asian American stories. She worked as an editor for 10 years at KoreAm Journal, a national Korean American magazine, and served as its editor-in-chief from 2011 to 2014, during which time she led award-winning coverage of the 20-year anniversary of the Los Angeles riots. She has written for the Hartford Courant in Connecticut, the Rafu Shimpo, a Los Angeles-based Japanese American newspaper, and the Los Angeles Times. Her feature stories have earned her awards from New American Media and the Society of Professional Journalists. In 2018 the Korea Economic Institute of America honored her for her contributions to journalism. A graduate of UCLA, where she studied English-American Studies and worked as a student editor, she is a past board secretary of the Asian American Journalists Association, Los Angeles Chapter, and a founding board member of the late ’90s reboot of Gidra, a progressive Asian American magazine that originated in 1969. Free Chol Soo Lee marks her first documentary film project.

DIRECTOR/PRODUCER – Eugene Yi

Eugene Yi is a filmmaker, editor, and journalist. His film editing work has premiered at the Berlin International Film Festival, the Sundance Film Festival, the TriBeCa Film Festival, and others. Selected titles include the News and Documentary Emmy-nominated Farewell Ferris Wheel, a documentary about guest workers in the carnival industry, and Out of My Hand, a fiction-documentary hybrid that was nominated for an Independent Spirit Award, and won the Grand Jury Prize at the 2015 Los Angeles Film Festival. His web video work has been in The New York Times, CNN, Frontline, the Washington Post, Buzzfeed News, Al Jazeera, and Deadspin. He served as assistant editor on Inside Job (2010), which won the Academy Award for Best Documentary. He was named one of the 2017 National MediaMaker Fellows with the Bay Area Video Coalition, for Free Chol Soo Lee. He teaches at the Edit Center, a school for film editing based in Brooklyn. Yi’s print journalism has been honored with numerous awards, including the LA Press Club Award for his oral history of the 1992 Los Angeles unrest from the Korean American perspective for KoreAm Journal. He is a native of Los Angeles and a graduate of Brown University, where he studied neuroscience.