Cured

Description

Mentally ill. Deviant. Diseased. And in need of a cure.

These were among the terms psychiatrists used to describe lesbians and gay men in the 1950s, 1960s, and early 1970s. According to the medical establishment, every gay person—no matter how well-adjusted—suffered from a mental disorder. As long as lesbians and gay men were “sick,” progress toward equality was impossible.

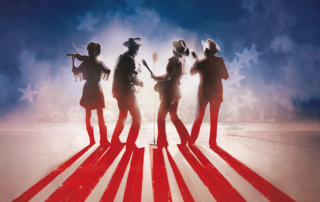

CURED chronicles the battle waged by a small group of activists who declared war against a formidable institutional opponent—and won. This feature-length documentary takes viewers inside the David-versus-Goliath struggle that led the American Psychiatric Association (APA) to remove homosexuality from its manual of mental illnesses. Viewers will meet the key players who achieved this victory, along with allies and opponents within the APA. The film illuminates the strategy and tactics that led to this pivotal yet largely unknown moment in the movement for LGBTQ equality. Indeed, following the Stonewall uprising of 1969, the campaign that culminated in the APA’s 1973 decision marks the first major step on the path to first-class citizenship for LGBTQ Americans.

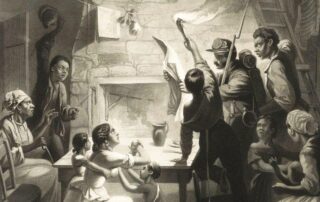

The film opens with archival images and personal testimony that portray what life was like for gay Americans in the 1950s and 1960s. During this era, most lesbian and gay people lived in the shadows because they faced discrimination, isolation, and criminal prosecution. Many got married to hide their identities. Nearly all lived in fear.

Underlying this bleak outlook was a fundamental reality: Even progressive psychiatrists considered homosexuals abnormal, because the “bible” of psychiatry—”The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders,” or DSM, first published in 1952—classified homosexuality as a “sociopathic personality disturbance.” The consequences of this diagnosis were dire. Gay people were subjected to castration, hysterectomies, electroshock, and lobotomies. Those who managed to avoid such severe treatment often spent countless hours trying to get “cured”: Charles Silverstein, one of our storytellers, saw a psychiatrist three times a week for seven years, hoping to become heterosexual and safeguard his job as a 5th-grade teacher. Rev. Magora Kennedy, another storyteller, recounts the choice her mother gave her upon discovering Magora’s attraction to girls: Marry a man or be institutionalized. Kennedy chose to get married—at 14.

Before almost anyone else, Dr. Frank Kameny understood that the gay rights movement had to get the DSM classification changed to achieve progress. Kameny had been fired by the federal government in 1957 because he was homosexual; his superiors were enforcing President Eisenhower’s 1953 Executive Order that banned homosexuals from federal employment. That injustice motivated Kameny to become an activist. A Harvard-trained astronomer, Kameny argued that there was no empirical basis for the illness theory of homosexuality: “If they felt it was a disorder or a pathology, fine, let them present their good, sound, solid, scientific evidence to show it. They never did!”

By the late 1960s, a new generation of lesbians and gay men was fighting back, inspired by the civil rights, anti-war, and women’s movements. Among them was Don Kilhefner, a UCLA graduate student who led a “zap,” or protest, at a 1970 aversion-therapy conference in Los Angeles. As Kilhefner recounts, the activists not only took over the meeting—with the SWAT team stationed outside—but then invited therapists to engage in dialogue, marking the first time these doctors ever spoke to gay people who did not consider themselves sick.

The activists’ message reached a national audience in 1971, when seven lesbians appeared on PBS’ “The David Susskind Show.” When Susskind refers to “the body of medical evidence that suggests [homosexuality] is a mental aberration,” Rev. Magora Kennedy challenges him, asking Susskind if classifying homosexuals as mentally ill “makes you feel good.” Barbara Gittings, a tenacious organizer who worked closely with Frank Kameny, joined Kennedy on the panel, insisting to Susskind that “the body of knowledge which claims sickness for homosexuality has to be challenged.”

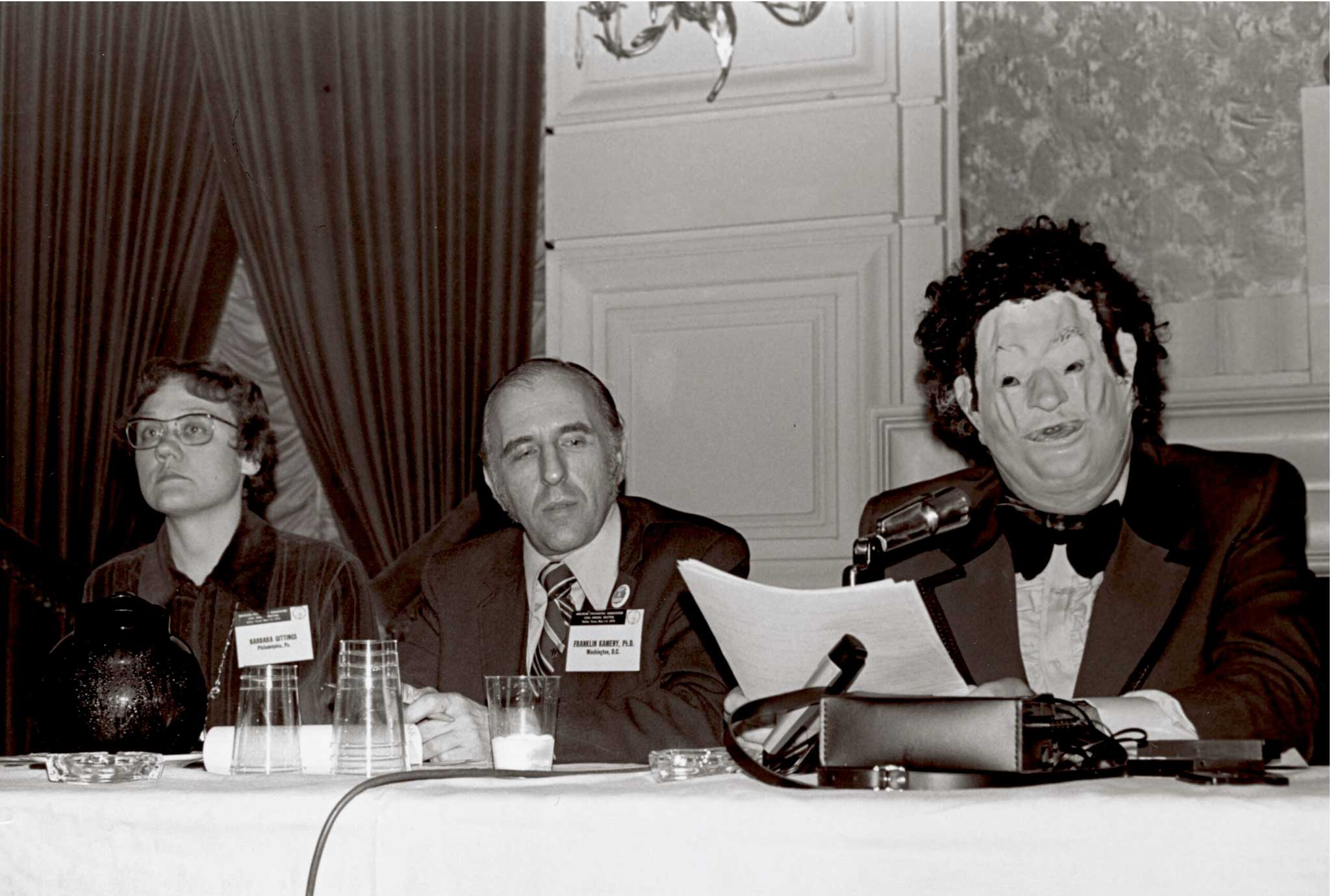

Amid mounting protests, the APA decided to have a more comprehensive discussion of homosexuality. That’s how Gittings ended up organizing an unprecedented panel at the APA’s 1972 convention in Dallas. She tracked down a gay psychiatrist who agreed to participate—but only on the condition that he remain anonymous. Wearing an oversized Nixon mask, “Dr. H. Anonymous” stunned his colleagues by describing his tormented experiences as a closeted gay therapist. Kay Lahusen, Gittings’ partner of 46 years and one of our storytellers, characterizes this moment as “a game-changer” because—for the first time—APA members heard a personal story from a colleague who was both gay and a practicing psychiatrist.

As reform-minded APA insiders shifted their thinking, supporters of the mental-illness diagnosis stood their ground. Dr. Charles Socarides was the main force working to oppose the DSM change; he spent five decades trying to “cure” gay men and lesbians. The film chronicles his opposition through extensive archival material. We also hear from Socarides’ son Richard, a gay man who served as President Clinton’s advisor on LGBTQ issues.

In May 1973, the DSM fight shifted to Honolulu, site of the APA’s annual convention. Ronald Gold, another key storyteller, participated in a debate on the pros and cons of changing the DSM. Gold’s presence on this panel symbolized the activists’ progress: Instead of disrupting APA sessions, they were now part of the conversation. Gold didn’t hold back, however, even entitling his speech, “Stop it, you’re making me sick!”

After continued lobbying and additional deliberations, the APA Board of Trustees voted unanimously in December 1973 to “cure” gay and lesbian people by deleting homosexuality from the DSM. Socarides and his supporters pushed back, engineering a referendum in the spring of 1974 for the entire APA membership to weigh in on the issue. When the ballots were counted, 57 percent of APA members had voted to affirm the board’s decision.

An epilogue chronicles the ways in which the DSM declassification—described by one reporter as “the greatest gay victory”—opened the door to dramatic changes. “We didn’t want kids growing up feeling bad about themselves,” reflected Charles Silverstein. “We were doing this for younger generations, not just for ourselves.”

Film Website: https://www.cureddocumentary.com/

About the Directors

Bennett Singer

Bennett Singer (Producer/Director) is an award-winning filmmaker who has been making historical documentaries for more than 25 years. He co-directed BROTHER OUTSIDER, a “potent and persuasive” (“Los Angeles Times”), “beautifully crafted” (“Boston Globe”) and “electrifying” (“MetroWeekly”) portrait of the gay civil rights activist Bayard Rustin. The film premiered at Sundance, aired on PBS’ POV series and on Logo, and won 22 international awards, including the GLAAD Media Award for Outstanding Documentary, eight Best Documentary prizes, and seven audience awards. Singer began his career at Blackside, Inc., where he worked for nearly five years; he received a duPont-Columbia Award for his work on EYES ON THE PRIZE II, the landmark PBS series on civil rights history. He later co-directed ELECTORAL DYSFUNCTION, a feature-length documentary about voting in America that aired nationally on PBS and was accompanied by an extensive engagement campaign. The film was featured in a four-part New York Times Op-Docs series and won multiple awards, including the Silver Gavel Award from the American Bar Association for a documentary that promotes public understanding of the law.

Patrick Sammon

Patrick Sammon (Producer/Director) has a mix of experience in filmmaking, broadcast journalism, and LGBTQ political advocacy. The president of Story Center Films in Washington, DC, he is Creator and Executive Producer of CODEBREAKER, a “superb” (“The Telegraph”) drama-documentary that “artfully explored” (“The Mail”) the life and legacy of gay British codebreaker Alan Turing. Sammon turned his concept for CODEBREAKER into an acclaimed film that has attracted more than three million viewers worldwide (www.turingfilm.com). He started his career as an award-winning television news reporter at CBS affiliates in Northern New York and Northeast Tennessee. After that, he served as President of an LGBT political organization in Washington, DC.